Des O'Brien

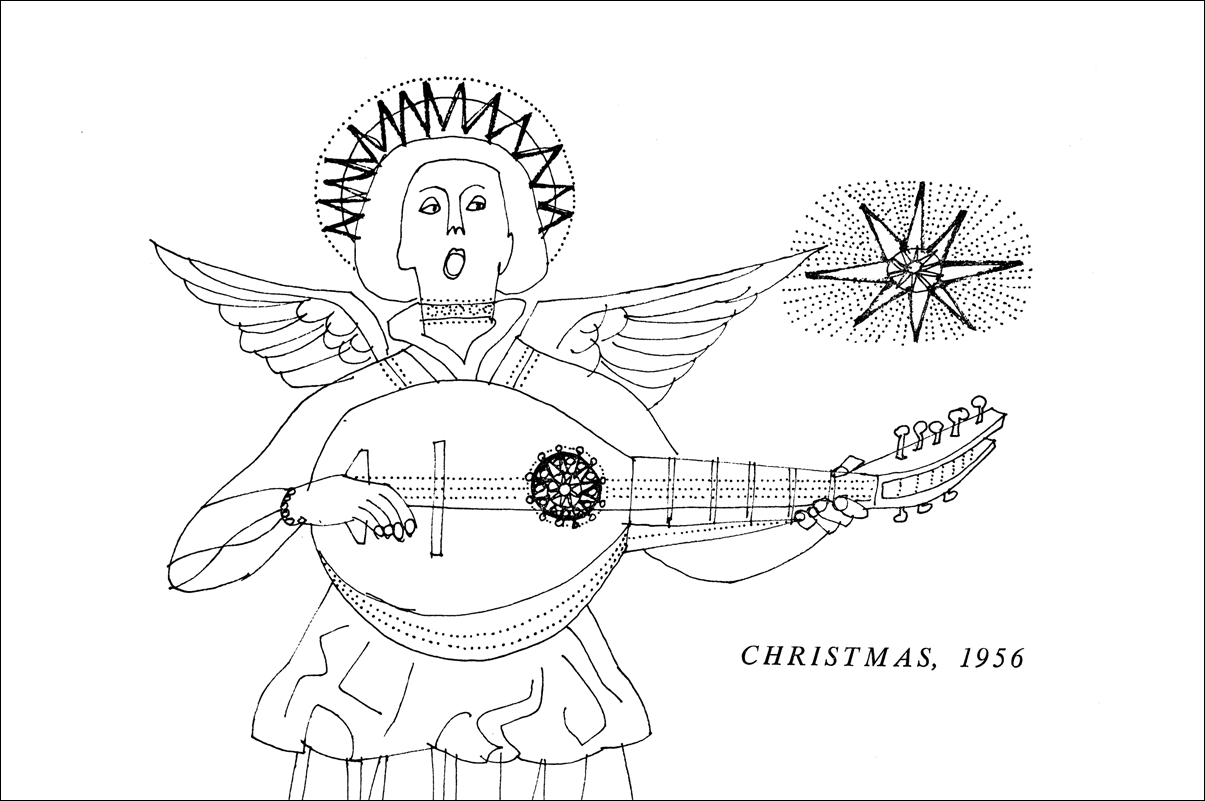

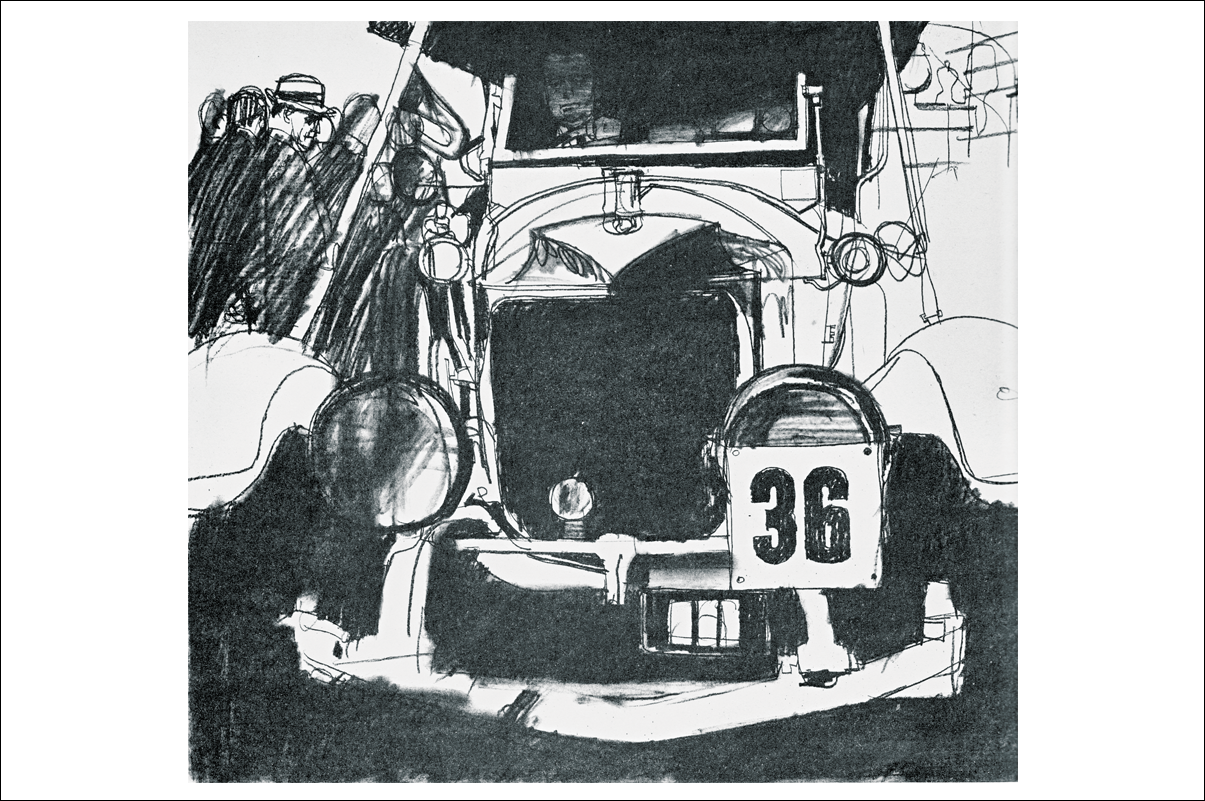

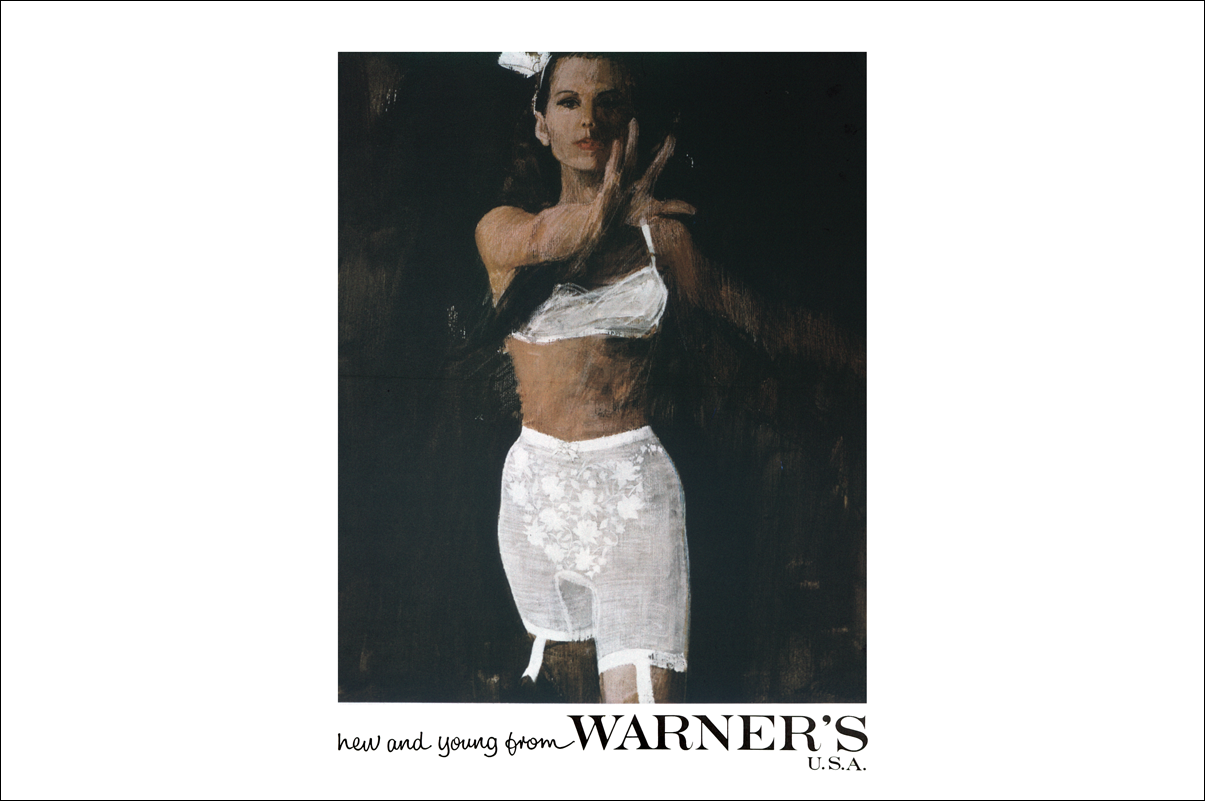

Des O’Brien was one of Australia's most respected editorial and institutional illustrators. He is a recipient of a Bronze Medal from the Arts Festival of the Melbourne 1956 Olympic Games, the author, designer and illustrator of the children’s picture book The Frog and the Pelican awarded a Bronze Medal from Leipzig in 1983 and the Australian Book Publishers Design Award. He was inducted into the Illustrators Hall of Fame in 1995. After which he worked almost exclusively on his personal art and producing limited edition artists books of his work.

The artist/designer/author was born in Sydney and studied at the National Art School Darlinghurst.

Excerpt from The Illustrators Association of Australia Book 5

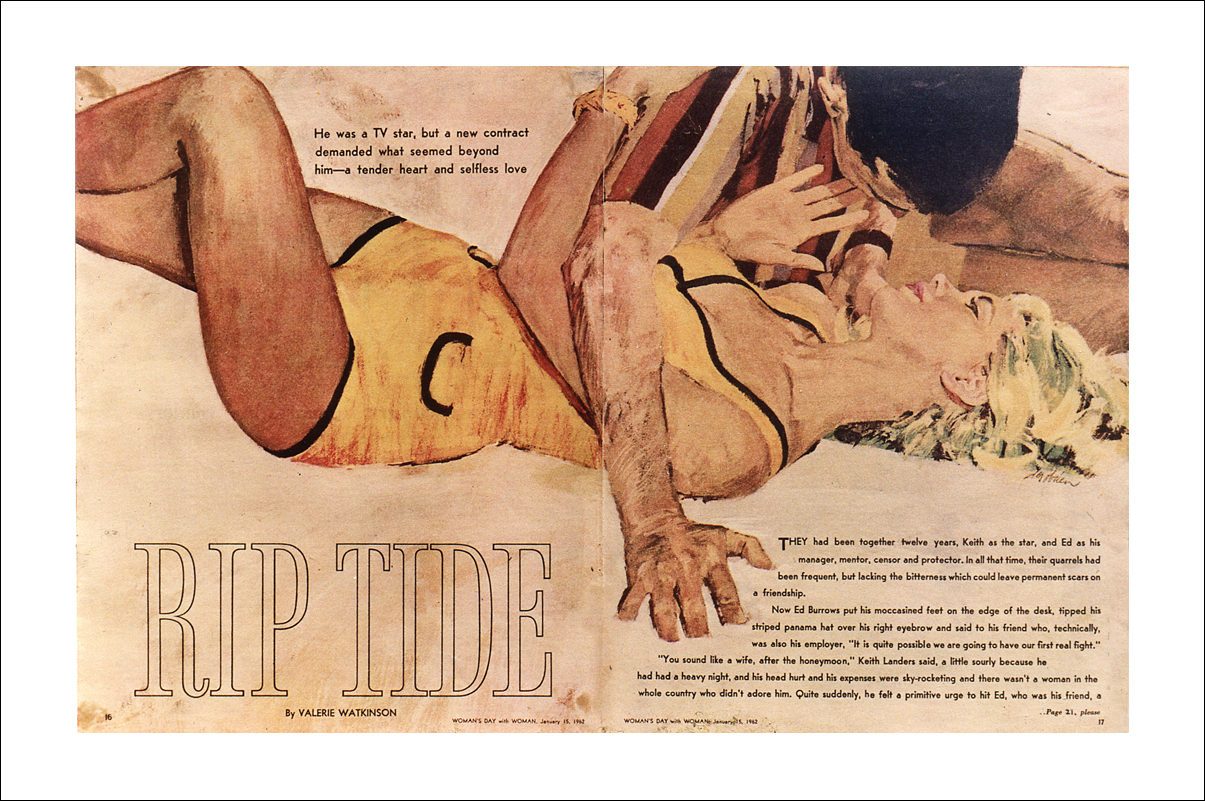

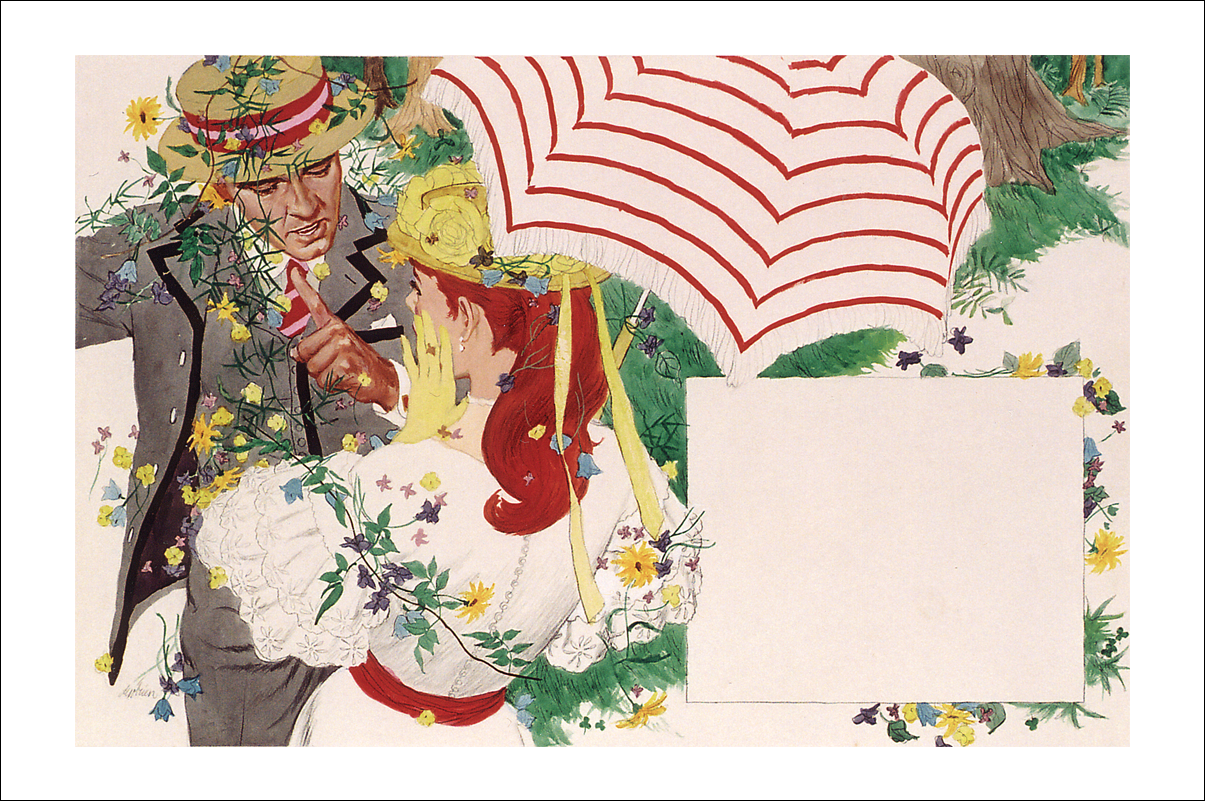

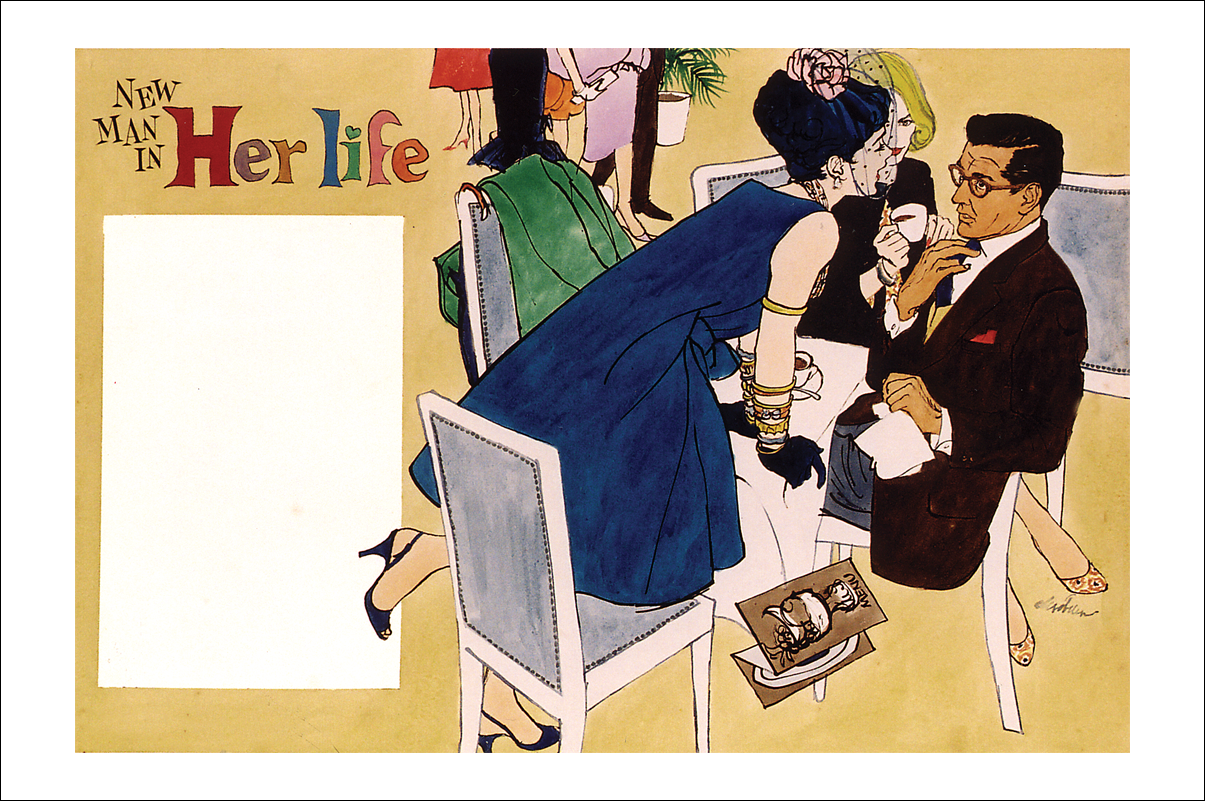

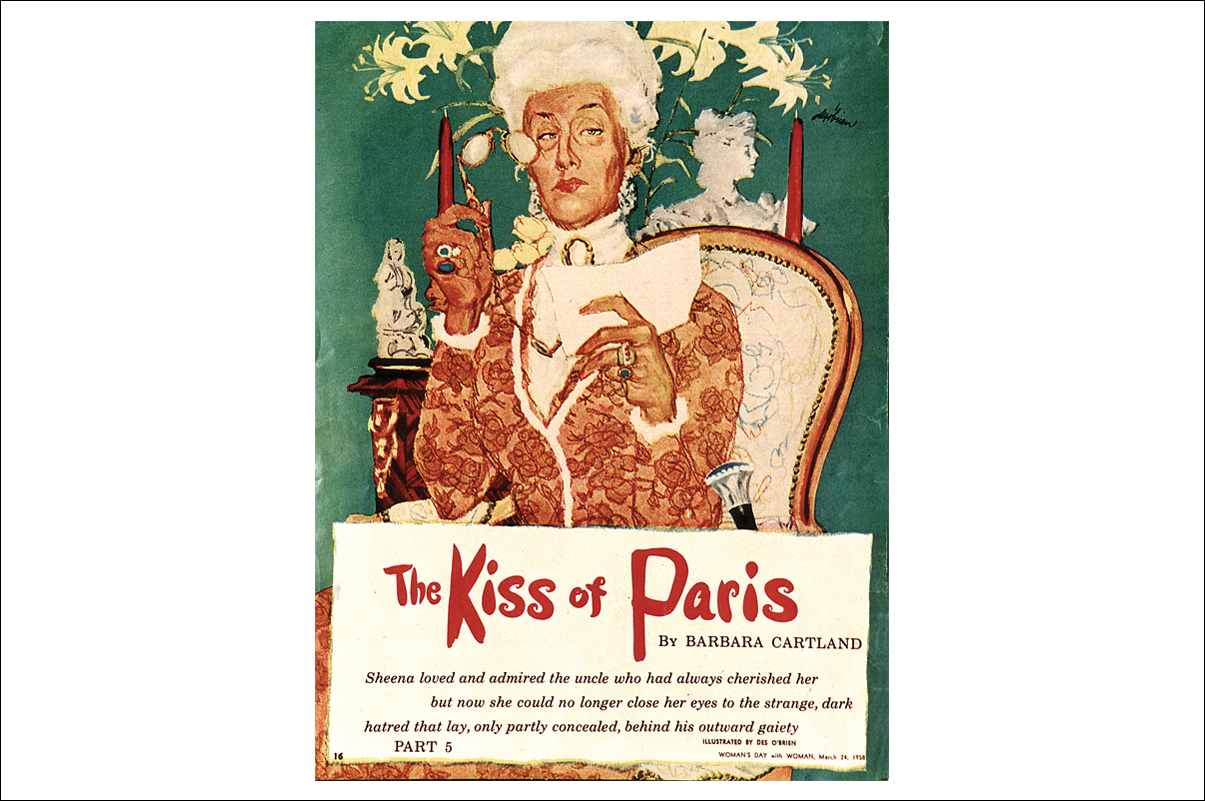

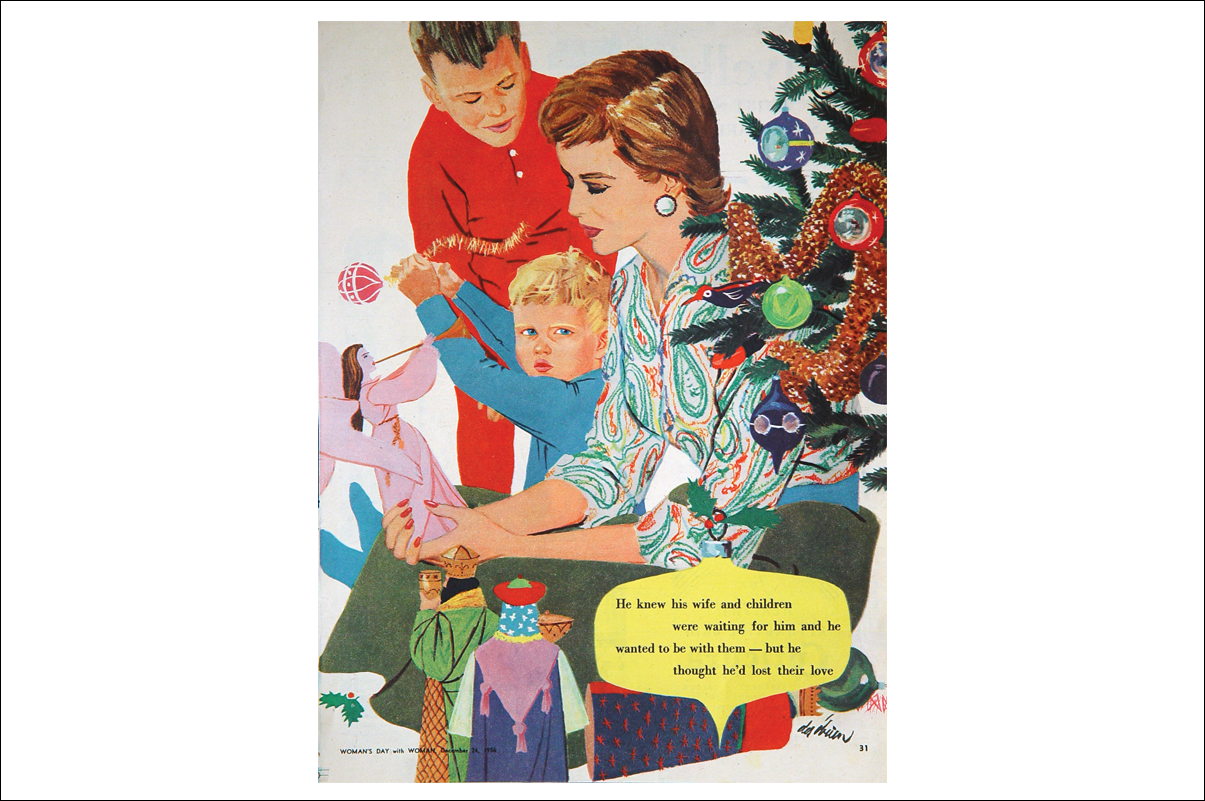

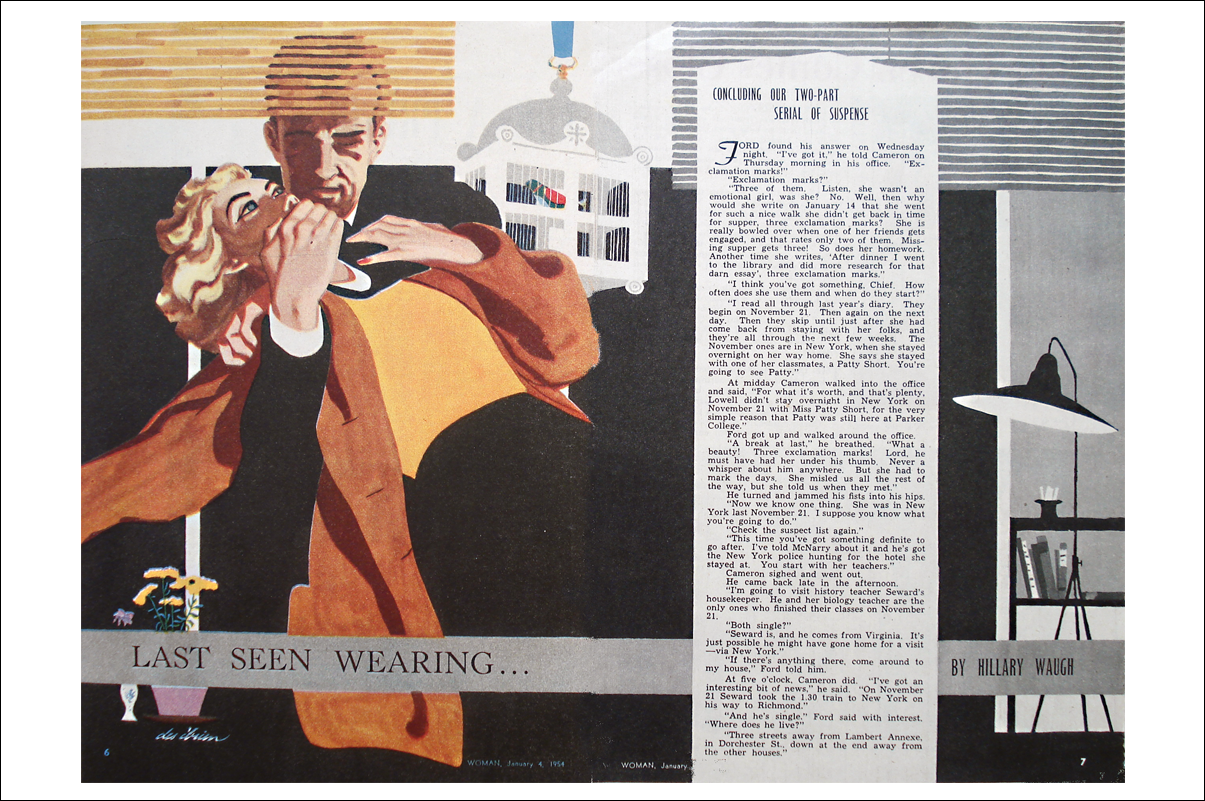

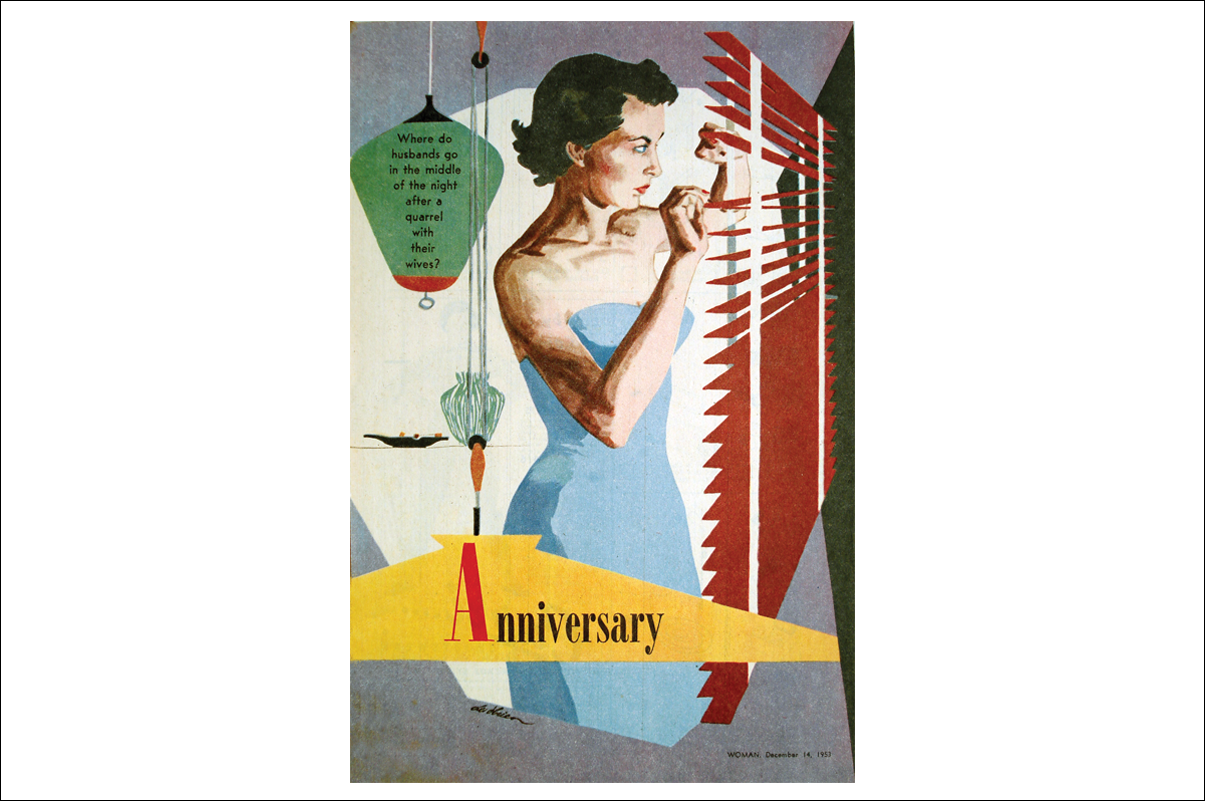

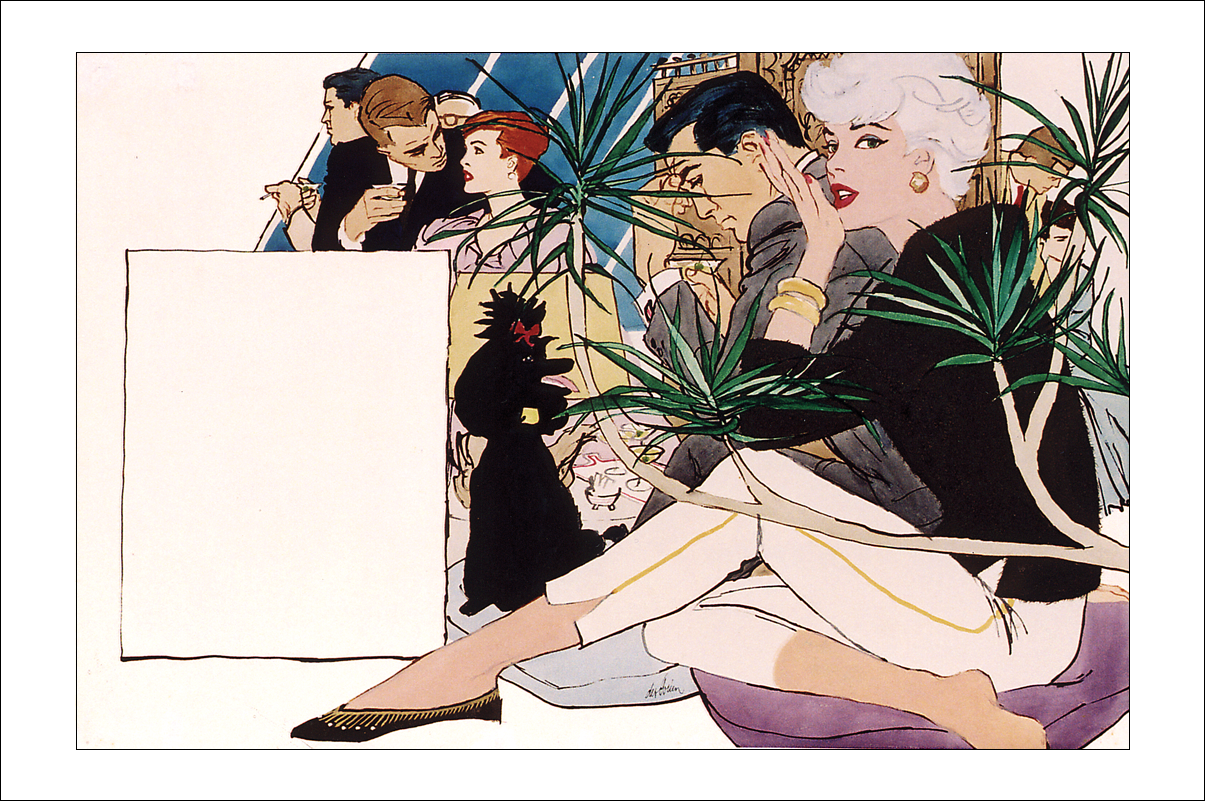

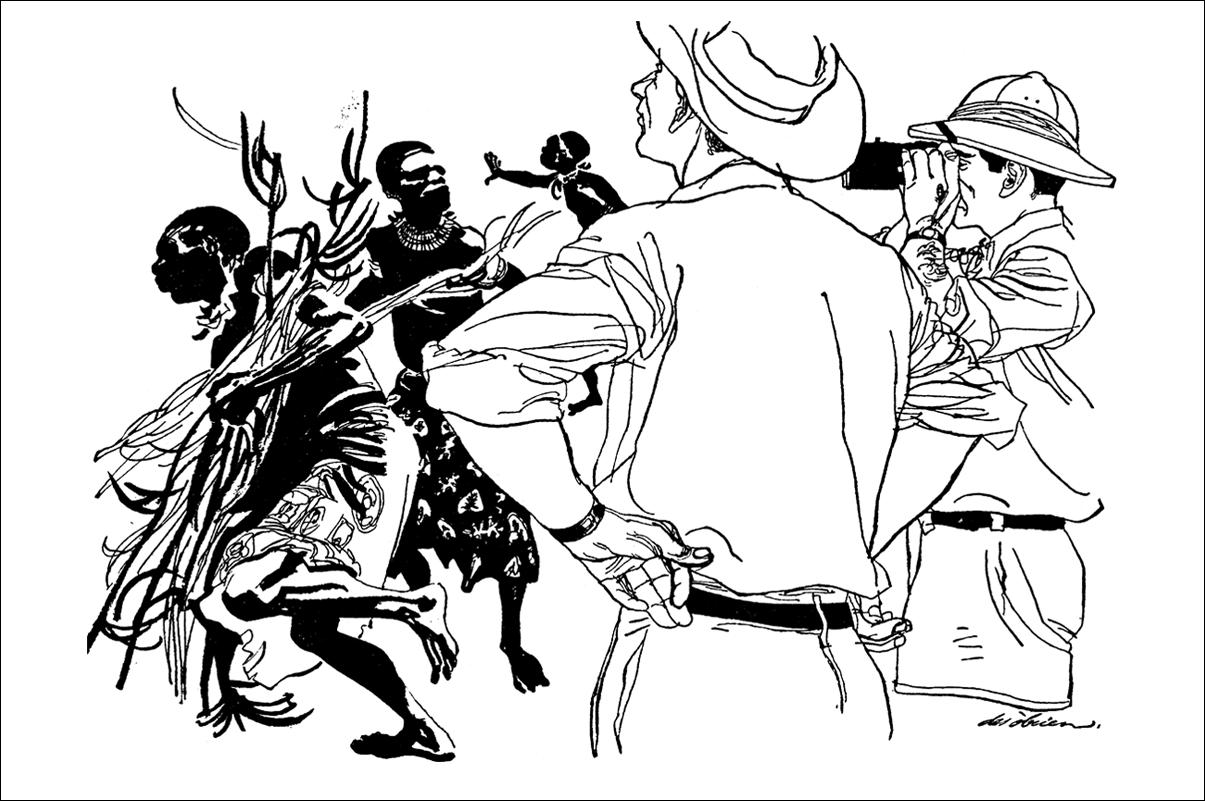

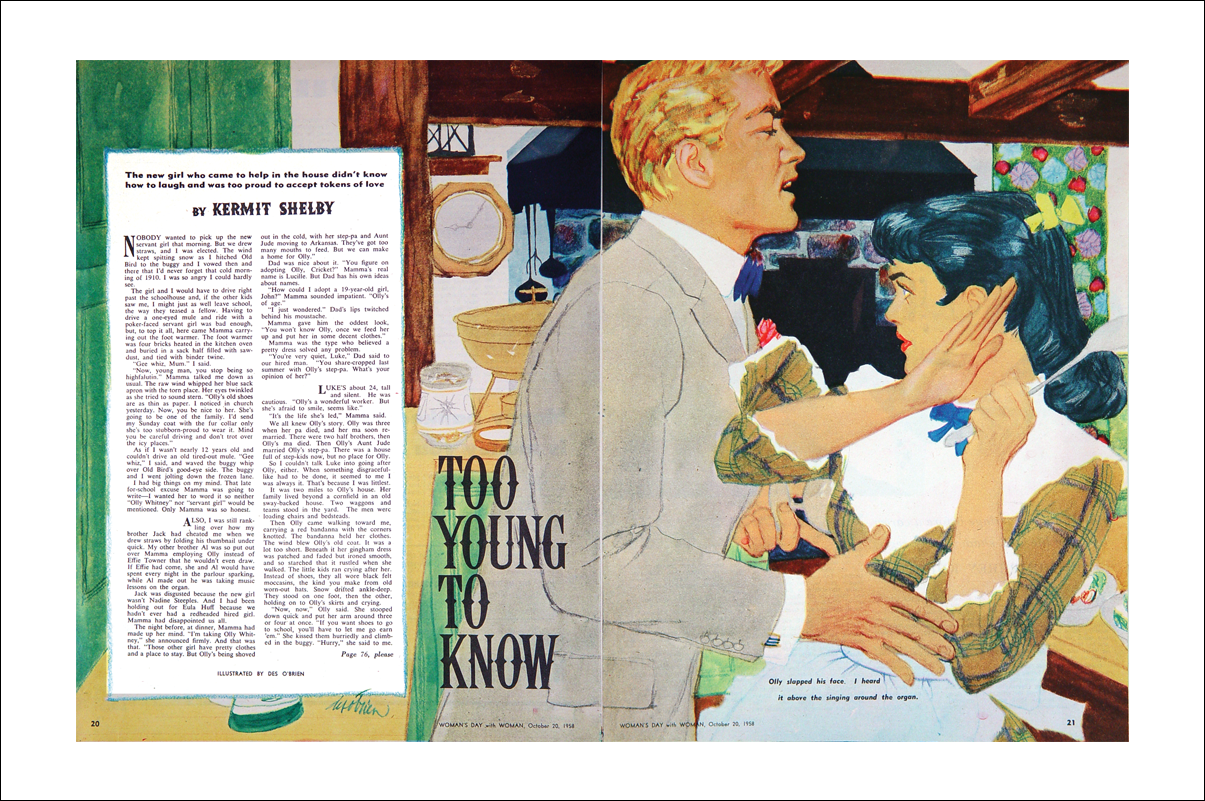

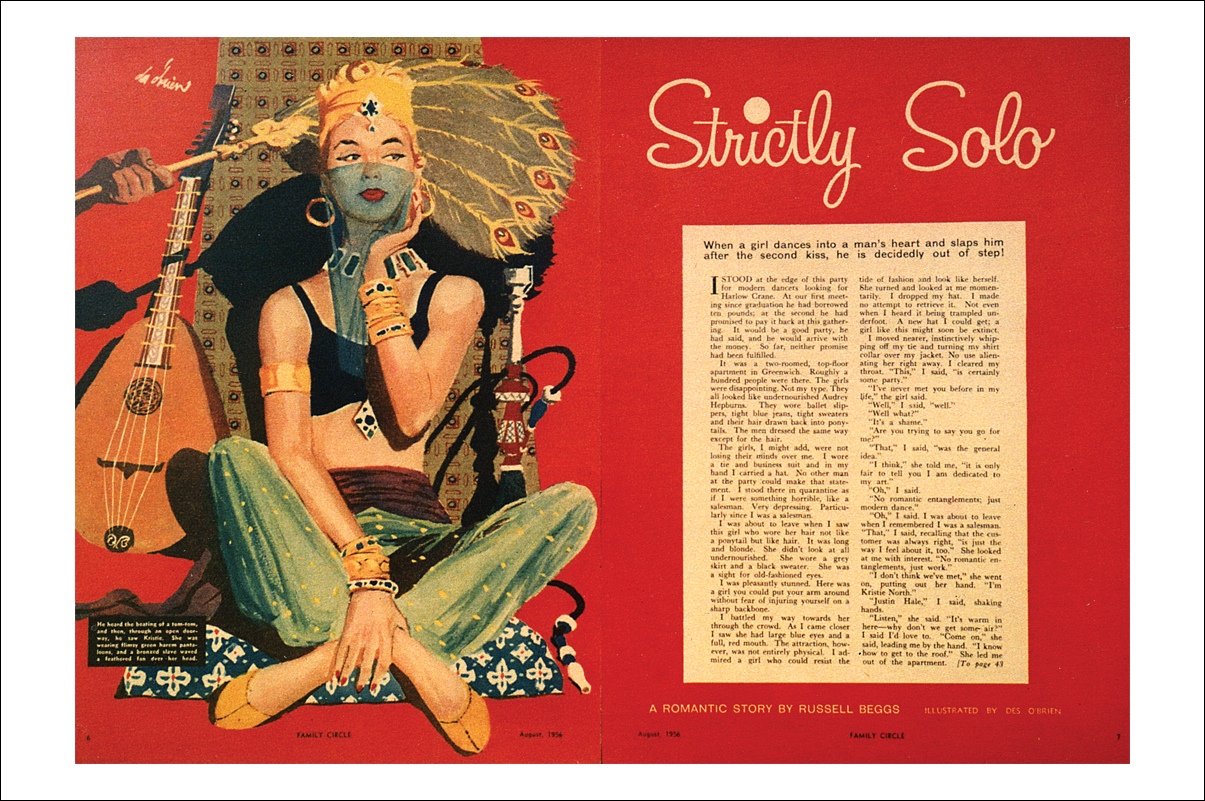

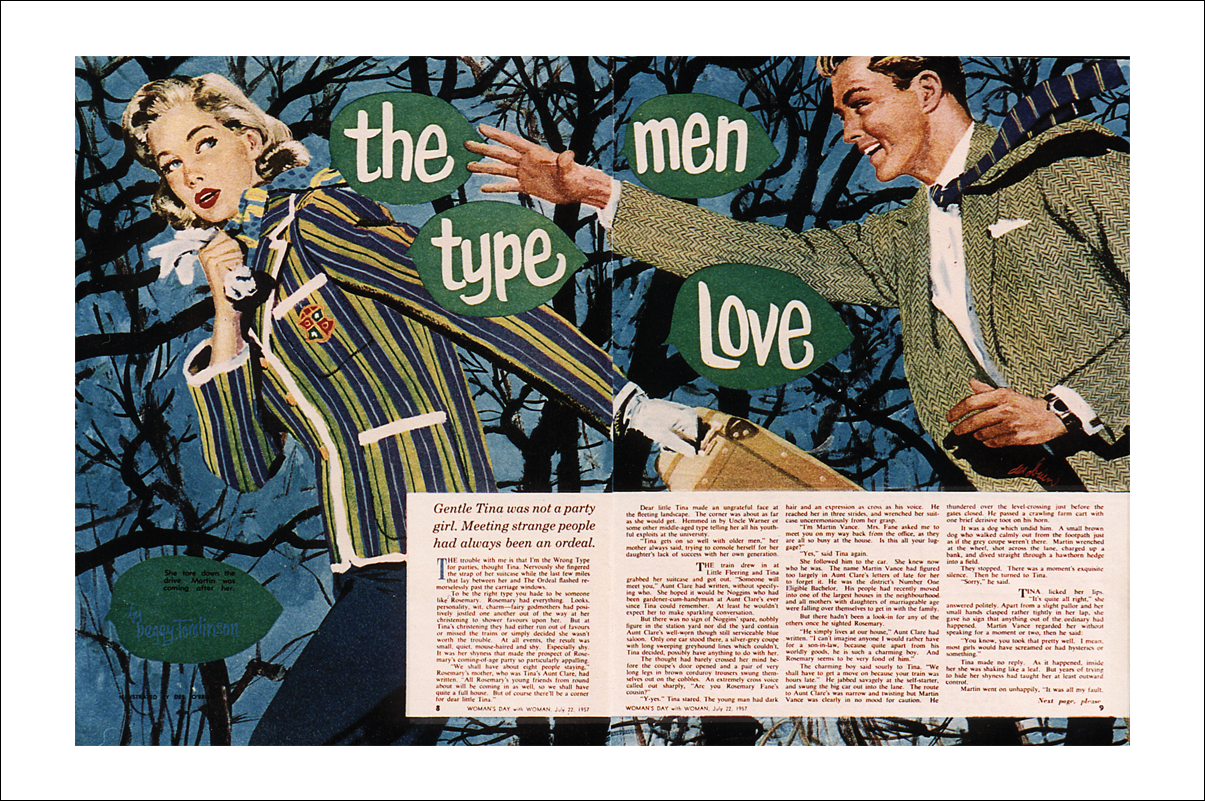

Des O’Brien worked in the heyday of Australian illustration through the 1950s and 1960s, when a strong magazine industry, using illustration, flourished in Australia. It was also an era when many talented artists worked in the field at the same time. For sheer excellence of output, Des O’Brien dominated this field.

I have been privileged to see almost all of his original works over nearly 36 years and I believe, at his best, he is potentially the most gifted illustrator Australia has produced since World War II. His work is always distinguished by apparently effortless, fluent draftsmanship, coupled to sensitive design and use of colour, all culminating into elegant and authoritative illustrations.

He refuses to use mechanical aids, or to project or trace anything down, always drawing directly onto the board and starting again, many times over, till satisfied. A perfectionist and a master of many mediums, he set very high standards for himself and the pace of his peers.

For my generation, he certainly was a hard act to follow.

Connell Lee / Illustrator

Click arrows to scroll

The Early Years

The following text is the introduction to Des O'Brien The Early Years 1951 – 1955. An artist book by Des on his years illustrating for Associated Newspapers.

I was born at home, in Sydney’s Eastern Suburbs. The Sydney Harbour Bridge was almost completed and Charles Kingsford Smith flew over the Pacific ocean to America. Our film industry was booming with such movies as Dad and Dave and Forty Thousand Horseman. The Depression had started. My journey with Associated Newspapers began with my father reading the Sunday colour comics to me with my favourite Ginger Meggs on the front page. Every time I went into the city with my mother by tram, she pointed to the big golden painted sphere on top of a building, “Look, that’s where Ginger Meggs comes from.” I rarely drew as a child, but remember doing a drawing for Sunbeams in the comic section. I received a letter from a girl in the country saying she liked my drawing and could I visit her during the Christmas holidays when her family comes to Sydney. My parents hounded me to go. When we met, she looked at me, giggled and ran back into the house, slamming the door in my face. I never ever sent another drawing to Sunbeams.

Towards the end of the war, the political cartoons of Stuart Peterson’s in The Sun took my attention, one in particular, I tried to copy. My father (sensing my interest in a possible career), somehow arranged for me to meet him. Excited, I took with me a drawing of his I’d copied. His small office off a larger one where an artist was working, was filled with his cartoons spread all over the place. He was seated at his desk colouring them all in with watercolour for an exhibition of his work. He gave me the original of the cartoon I admired so much, signed with his complements and a chinagraph pencil he used as a tone on his drawings. Such generosity astounded me. I have never forgotten. Then he introduced me to the artist working on an illustration for an advertisement in the outer office, Walter Jardine. They both were kind enough to take an interest and advise me about a career in art. Encouraged by this I started submitting drawings to the Bulletin. Ted Scorfield the resident cartoonist asked to see me. I was invited to the Friday afternoon sessions where the cartoonists would bring in their weekly cartoons. I met Unk White, Percy Lindsay (Norman’s brother) and others. Ted Scorfield showed me many originals of Phil May, Norman Lindsay, Low and Hop. They were exciting days. I learnt it was the drawing that interested me, not the joke.

In my second year at high school I enrolled for a Saturday morning art class at The National Art School, East Sydney. I sold some cartoons to The Sun for their “Smile a Day,” and decided not to continue high school on the advice of Frank Medworth, Principal of The National Art School, who initiated the Saturday morning art class.

Click images to enlarge

I took odd jobs during end of year holidays to earn money for the year ahead. At the end of second year, when a decision had to be made to do painting, design or the new course; Illustration and Commercial Art (up until then I wanted to do painting for the next three years). I got a job at Associated Newspapers, hoping it would help to make up my mind. They put me in Accounts. Personnel said it was the best place to learn all about the newspaper business. Every week I set the boardroom out with pencils and doodle pads for members of the board, around a huge oval table. I had to meet the chairman, Sir John Butters when he arrived downstairs in his chauffeur driven Rolls Royce, to carry his brass fitted empty briefcase up to the boardroom and down again after the meeting, with the pencil and doodle pad inside. On the occasions I needed to speak with Sir Hugh Denison (a tobacco manufacturer turned newspaper proprietor, who founded Sun Newspapers in 1910) he was seated behind a big desk in an office setting suitable to his position, complete with male secretary outside; there was never any chit chat.

Every Friday I went with two accountants (both were armed) to carry the bags full of money collected from two city banks for the weeks wagers; then helped to fill the pay packets. At Sungravure (the Rotogravure printing press that printed all the colour magazines and supplements) I handed out the pay packets to the plate-makers and retouchers. Over the time I spent there on Friday afternoons I got to know all about colour reproduction and printers complaints about artwork for reproduction; what and what not to do.

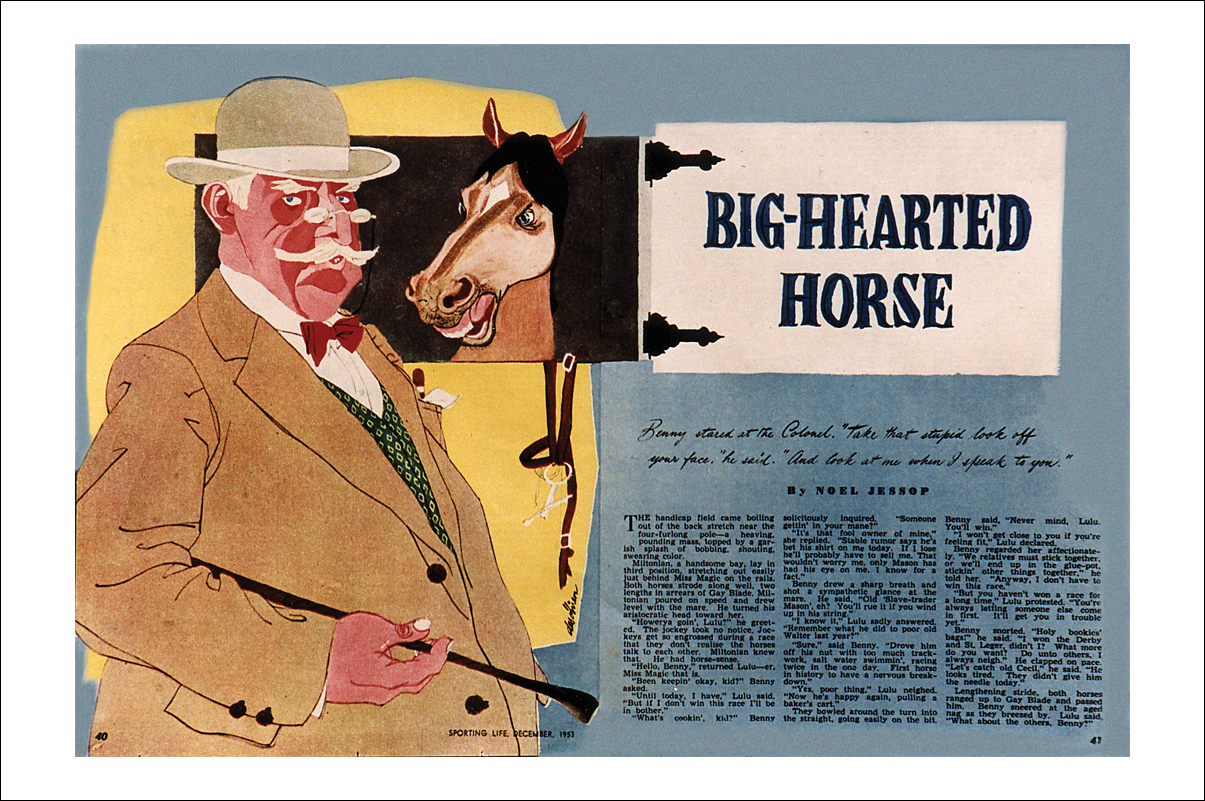

I was selected (after trials) by Keith Miller, then with Sporting Life, and Richie Benau, from Accounts to play on the office cricket team against the printers. We won, only just, both Keith and Richie advised me to join a local cricket club.

On my return to art studies I decided not to do the painting course but the newly formed commercial art course and continue life drawing with Godfrey Miller. A big mistake, my teachers Harvey and Badham warned me. If it wasn’t for Godfrey Miller I don’t think I would have continued. Later that year a job offer from a magazine publishers art director, wanting to employ an art student, was announced. I applied and was hired on my life drawings alone. I continued life classes in the evening with Godfrey Miller. In the three years I worked there I did layout, design, art direction and hand lettering. I put together a special magazine to be launched on the American market (a failure), then redesigned the fiction display pages: a completely different approach to page layout and instructions to freelance illustrators and my first published fiction illustrations.

All this led to an offer from Associated Newspaper’s art director Bill Knight to join their art staff as an A grade creative artist. I was first put in the layout department next to the Dutch creative artist, Kick, together with five layout artists. Altogether eight desks (one spare), making it pretty cramped. It was the very same room I met Walter Jardine in 1944, and Stuart Peterson was there doing his daily political cartoon in the room next to ours. The irony didn’t escape his attention.

Discover more about Des and his career in the applied arts from the book Des O'Brien – Ephemeral Aesthetics.

The Studio

Located on Sydney's Northern Beaches, for decades the studio operated as O'Brien & Horrex. An illustration and design firm run by Des and wife Jackie O'Brien, whom is known professionally by her maiden name of Horrex.

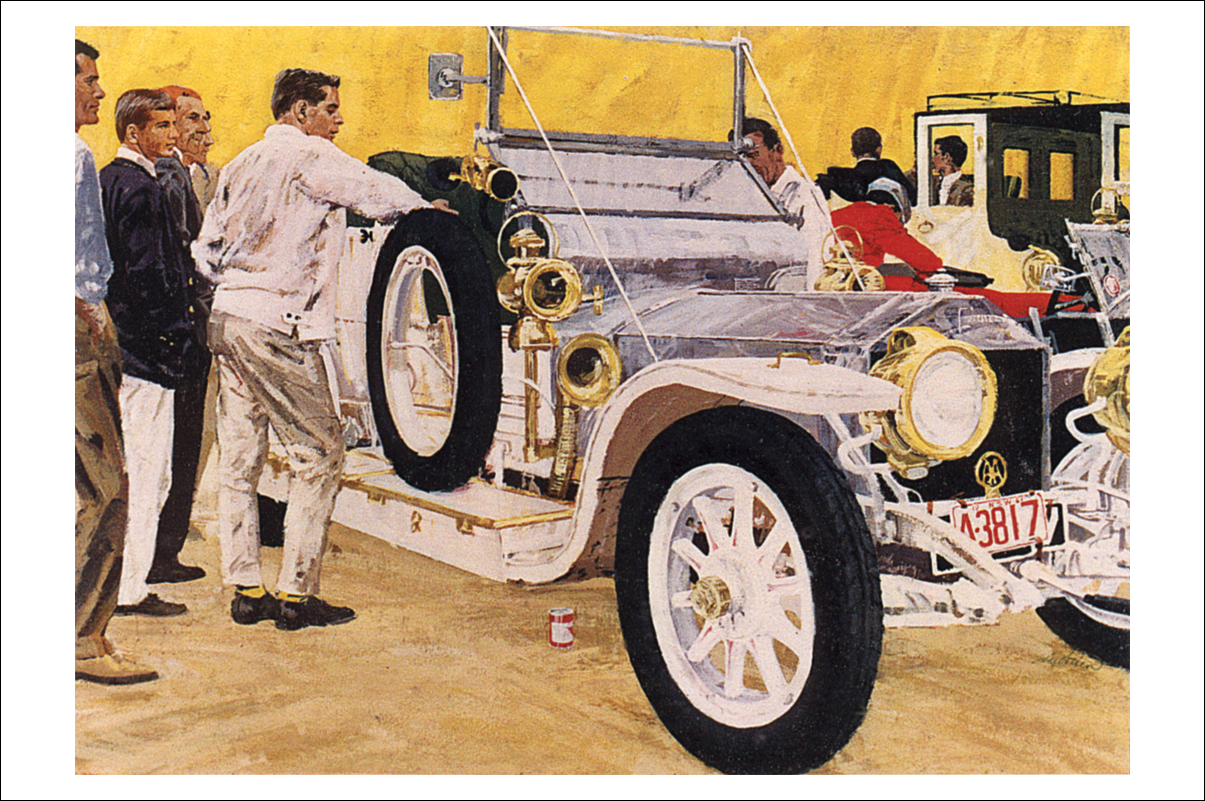

By 1958 both had left full-time positions to work for themselves. Their already established reputations in the field of editorial illustration provided them with a steady stream of work, which in the coming years they were able to expand upon and diversify. As their client list grew, so did the range of projects – advertising, fashion, graphic design, children’s books and postage stamps to name a few. All of which drew upon their illustration and design expertise.

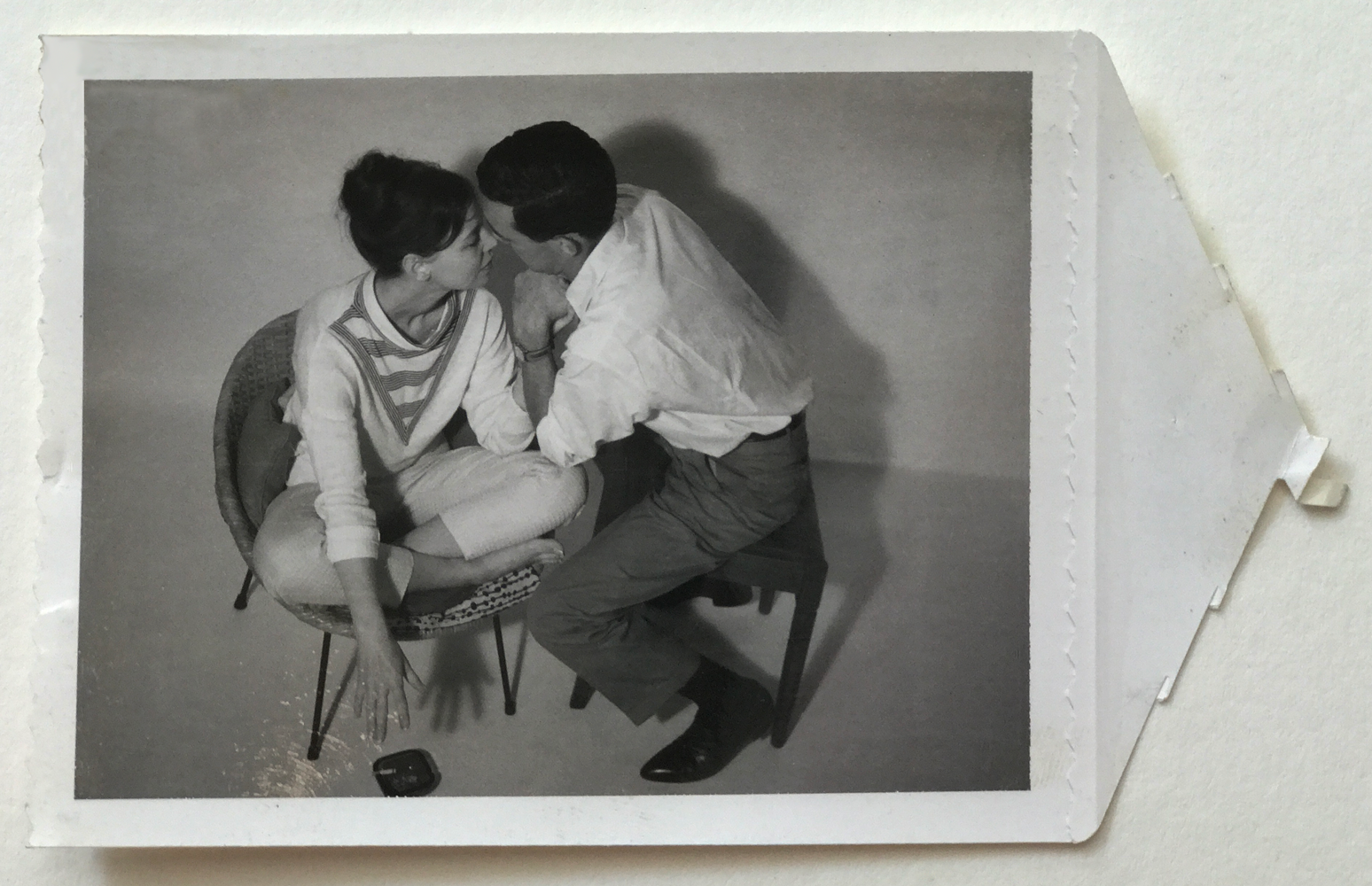

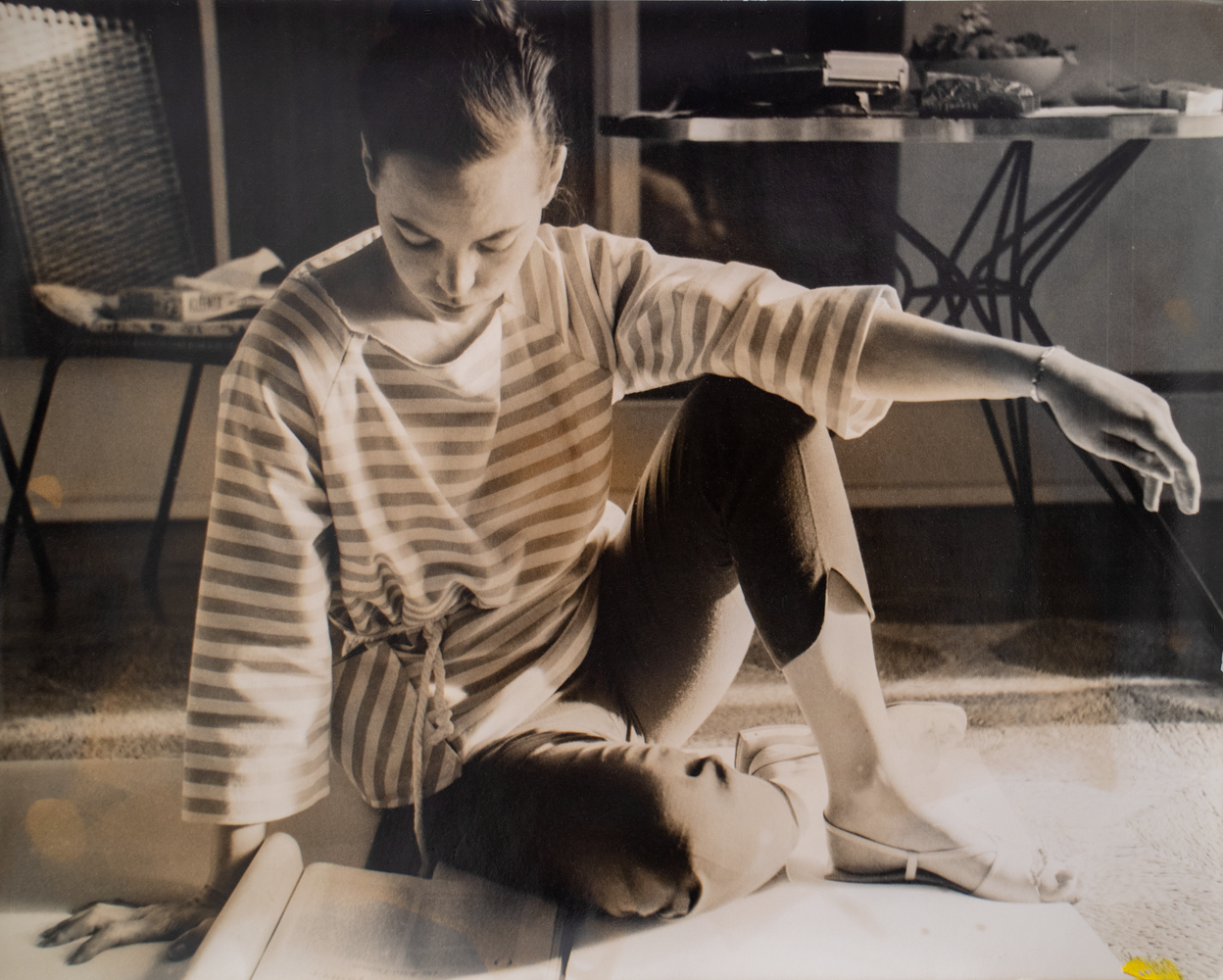

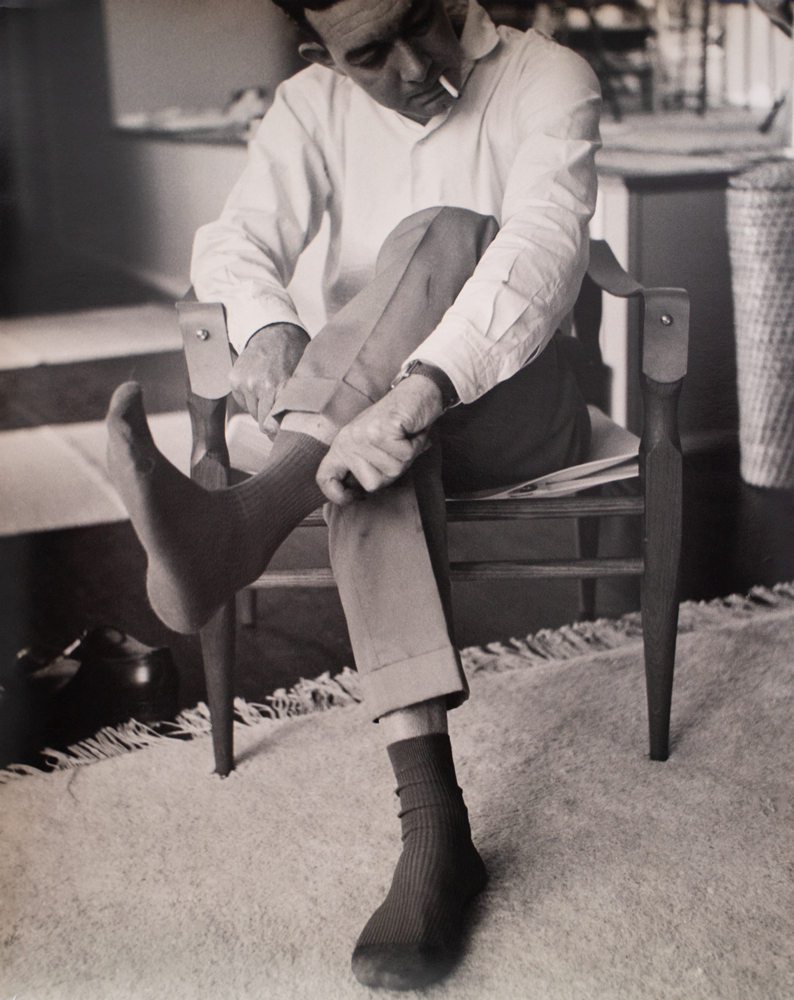

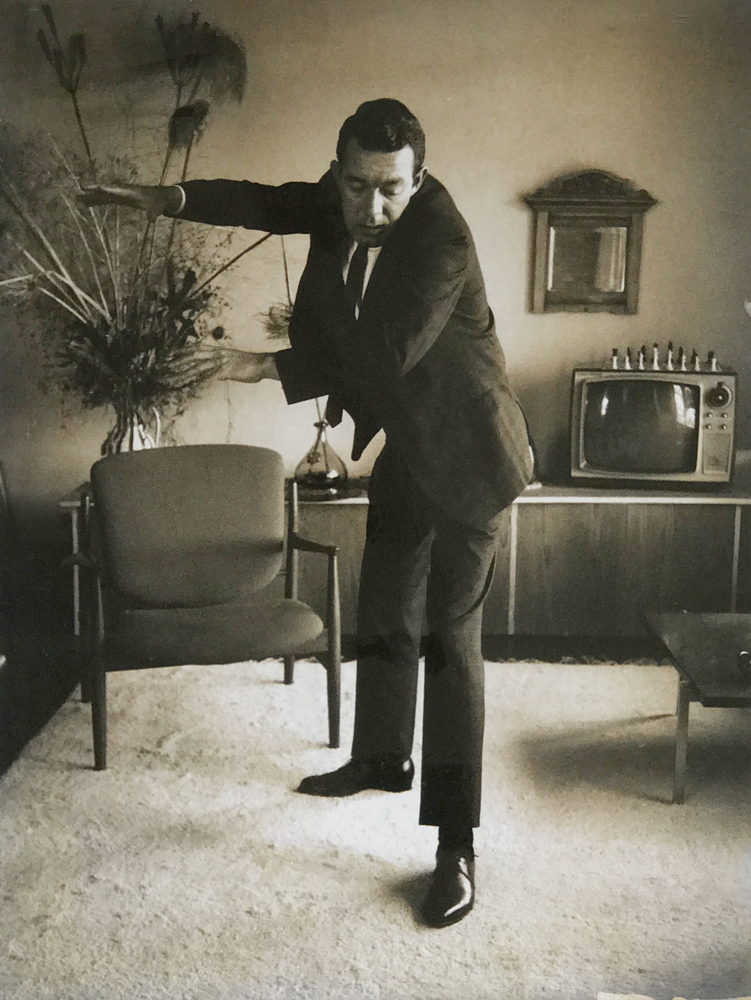

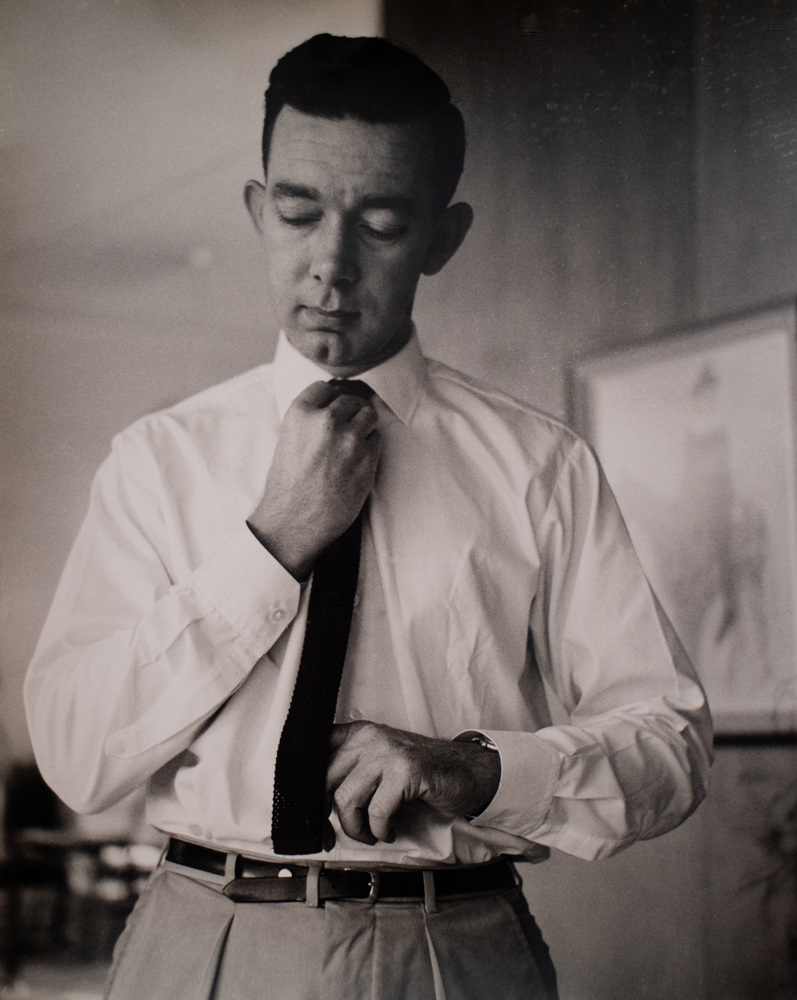

Adjacent to the studio was a darkroom where the two would develop their own photography, most of which was produced as reference for their illustrations. It was not uncommon for them to set up scenes that included themselves as models, with their home providing the perfect backdrop to modern life. Some of these images can be seen below in the slideshow.

They worked at the forefront of their field, and they embraced the new. Their surroundings were contemporary, filled with modern design, books, magazines, art and jazz. Conversation was lively, their view was a world view, and their extensive knowledge of art, fashion and design informed their work.

Over time they split their focus equally between their commercial work and their fine art. The studio easily accommodated this shift. Jackie, an accomplished watercolourist, continues to work here to this day. Des, a master of many styles and mediums has left a diverse body of work. Forever driven, open and passionate about pushing the boundaries of his work. There was never going to be enough time for him to achieve all he set out to do, but the time he had was definitely well spent.

“Call my illustration art. But don’t call my art illustration.”